I love Thai food. When I first moved to Boston, I lived across the street from Khao Sarn, and for a recently-gradutated college student that barely knew how to cook, their Pad See Ew became a staple dinner. After Khao Sarn closed, I transitioned to picking up from Dok Bua, a restaraunt that made up for the farther walk by including a mean hot sauce with every order. Dok Bua gave way to Equator and House of Siam as I moved across the city, and I even came to know Topaz Thai and Top Thai during the six months I lived in New York.

Recently, however, I feel as though I barely order Thai food at all. It hit me, the other day, during a conversation with my girlfriend. The conversation went something like this:

Me: You mind if we order Thai food for dinner tonight?

Karen: Sounds good to me!

Me: I feel like I never eat Thai anymore. Actually since we moved in together, I bet I have eaten substantially less Thai.

Karen: That’s possible! I’m down to order more Thai - I like Thai food.

Me: It’s your fault that I don’t eat Thai food anymore and I can prove it quantitatively.

Karen: Wait what

Me: Check the receipts I’m grabbing my credit card statements

Days later, after hours spent copy-pasting data from old PDF statements, writing code to clean up that copy-pasted data, and calling DoorDash to understand the ins-and-outs of their recent acquisitions and why their acquisition-related migrations mean I am no longer able to access my historical order data from their apps…

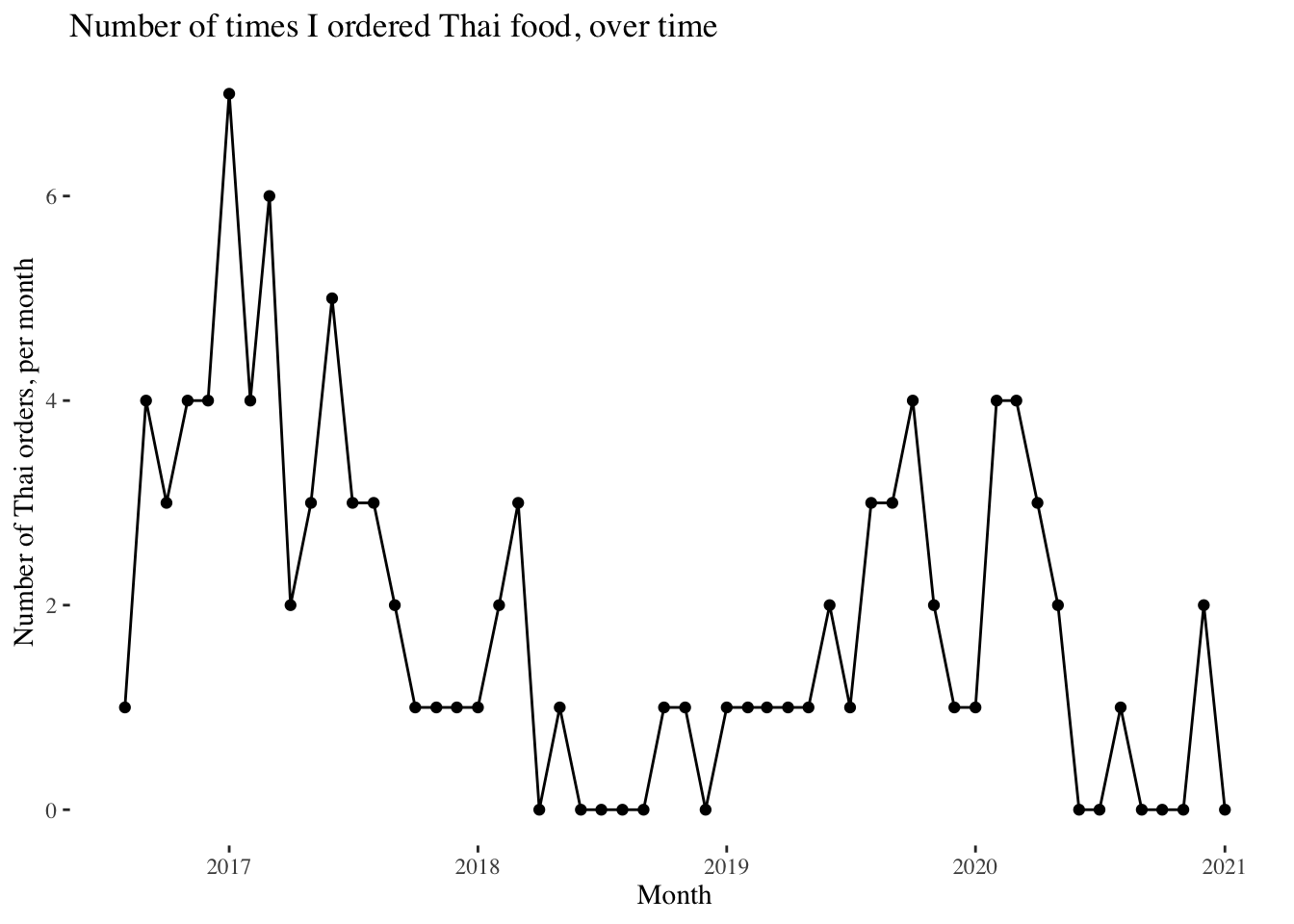

I have proof! Karen and I moved in together in late August, right around when my Thai habits plummeted. To be fair, the chart does show a dip in mid-2018, the exact time I was living in New York. Maybe I didn’t go to Topaz Thai as much as I thought, though given the amount of green curry I ate, I suspect we may be omitting the times that a friend placed the order, and I paid them back. Outside of that dip, though, this is the least amount of Thai food I have eaten in years.

I bring this to Karen.

Me: …

Karen: I see through you. This whole blog post is just an elaborate attempt to get me to agree to order Thai food more often. Which I am HAPPY to do!

Me: It sounds like you don’t believe the recent drop is relfective of a genuine trend in the data and is probably just due to random fluctuations in my Thai food habits.

Karen: That’s not at all what I am saying.

Me: Fine I’ll prove it more rigorously.

It should be fairly straightforward to use a hypothesis test to more formally demonstrate just how many fewer dumplings I have been able to eat.

Let’s start by defining our null-hypothesis: Suppose we were to assume that the average number of times per month that I would eat Thai food while living with Karen is about equal to the average number of times per month that I would eat Thai food while living alone. How much evidence do we have to disprove this null hypothesis (i.e. to show that the recent downtrend in Thai food eating is a real downtrend and not just a random fluctuations)?

Quick math break…

The bottom line? We have a lot of evidence. Assuming those random fluctuations would follow a normal distribution and running a standard t-test, it would be fairly unlikely (p-value of ~0.049) to see as few Thai orders as we do simply due to random chance.

This analysis took me about 5 minutes. While I would love to pretend that this was due to my amazing statistical skill, in reality it was because what I did was extremely surface-level. Pretending that running a quick hypothesis test will provide more of a moral high ground to blame my lack of Thai food on Karen made extraordinarily broad assumptions. Luckily, I know that as long as I use fancy math phrases like “independent and identically distributed”, I might be able to slip this one by her and convince her my work was quite rigorous …

On the other hand, she happens to be a third-year PhD student in a highly quantitative subfield of health policy, specializing in microsimulation modelling (read: seven billion times more complicated than the five minute hypothesis test I just did).

Karen: Seriously, we can order Thai food tomorrow - why are you doing this?

Me: So you’re saying you admit that moving in together led to me eating less Khao Soi Kai?

Karen: Look if you’re going to force me to engage, I think you have a remarkably poor quasi-experimental design, zero identification strategy, and therefore no possible ground on which to make any sort of causal claim that I am the reason you don’t eat Pad Thai. Can I go back to reading now?

Here is how I take the gist of Karen’s critique: “Sure, it may be the case that we haven’t ordered that much Thai food since September. Why are you putting that on the fact that we moved in together? Maybe you are ordering less Thai because we cook more (true), or maybe it has something to do with the fact that you started grad school at the same time we moved in together (also true)? There could be any number of other factors.”

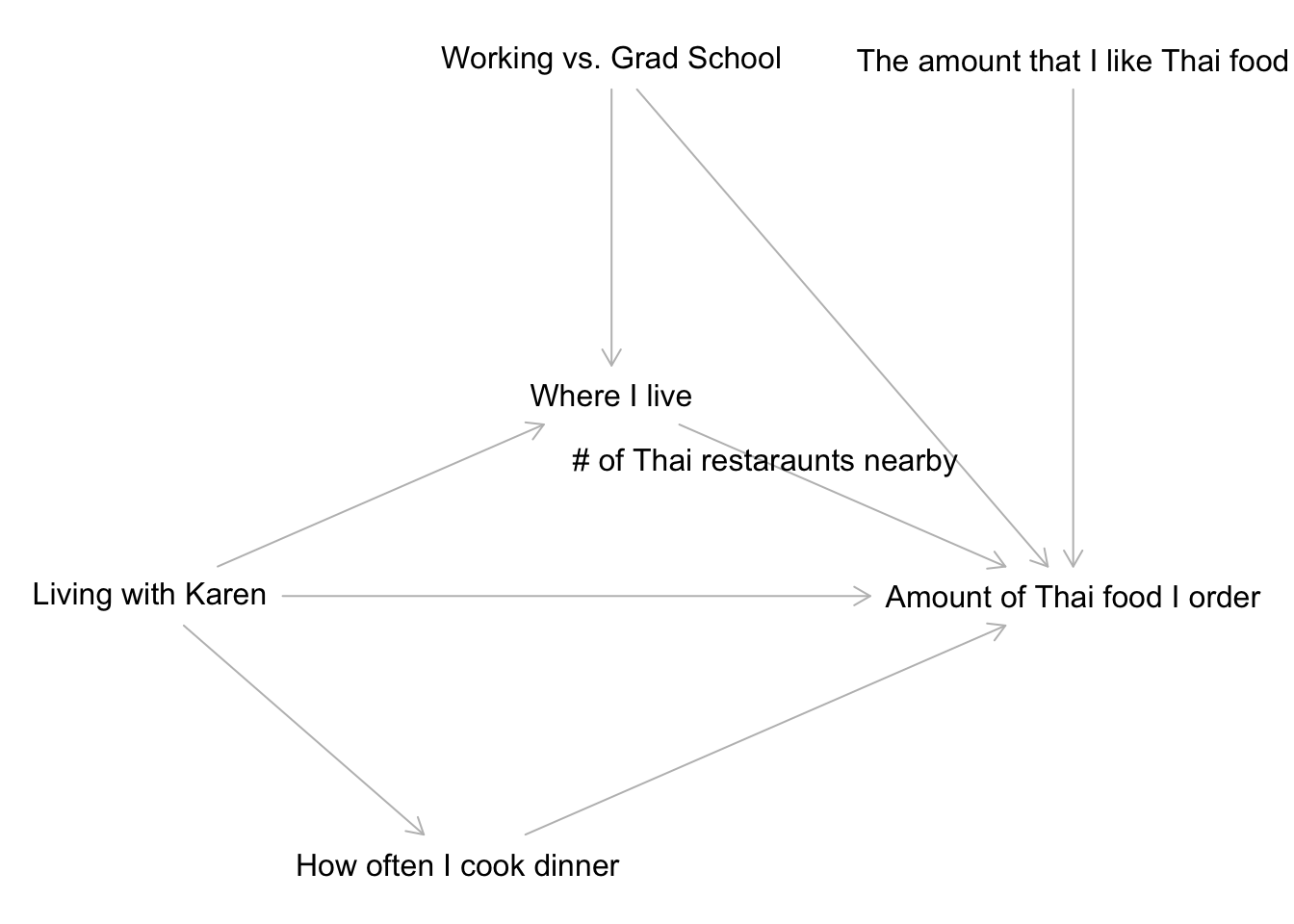

Proving causality is extremely difficult. However, a good place to start is to think carefully about all the variables involved and how they interact with each other. A DAG, or “Directed Acyclic Graph”, is a standard way to visualize those relationships. It sounds a lot fancier than it is - see the below DAG about Thai food for an example. The points on the chart represent the different variables (e.g. “How often I cook”), and the arrows represent causal pathways (e.g. “How often I cook” is likely to influence “Amount of Thai Food I order”). Naturally those causal pathways are assumptions, based on my best guess about what influences my Thai food ordering; they could be wrong!

Admittedly, there is a lot going on. But as we look closer, one key takeaway is that quite a bit runs through “Living with Karen”. How often do I cook dinner? Influenced by whether I am living with Karen. Where I live? Influenced by whether I live with Karen.

The problem child (for me) is that sneaky “Working vs. Grad School” variable. Before grad school I happened to be working at a job where I frequently stayed at the office past 8pm or 9pm at night (welcome to the world of management consulting!). When this happened, company policy allowed me to order dinner on the house. Plus, as I learned in one of my upper-level math classes in undergrad, the famous “Grubhub Theorem” states that “Free Food = More Thai Food Gets Ordered”. Naturally, this theorem holds independently of whether or not I am living with Karen.

Because of this, it is very difficult (if not impossible) to know whether my recent decline in Thai food is due to Karen or starting school, especially since I started school at pretty much exactly the same time that Karen and I moved in together. Plus, even if we did somehow deal with this problem, there is still the issue of “unmeasured confounders” or otehr unobserved variables. In layman’s terms, this basically means “There are probably a bunch of variables and arrows that I left off the graph that I didn’t think of”.

The bottom line to all of that is that I am not sure I will be able to prove that it is Karen’s fault after all. This is the bad news. The good news is that throughout the process I happened to uncover a separate causal mechanism that I feel quite confident in. To put it formally:

We have ordered more Thai food in the past two weeks than the last 5 months combined. I’m calling it a win.